While I favor Agorism, Voluntaryism, and Anarcho-Capitalism, I do have a solid knowledge base on the United States Constitutional Republic. This article will focus on normative foreign policy in this context, and later articles will deal with more philosophically palatable foreign policy questions. While I have studied politics and related topics intensely and broadly (my B.A. in Political Science represents the minority of my accumulated relevant knowledge), I do readily admit that I’m far from an expert on foreign policy. I’ll be learning as I write.

Let’s go through the U.S. Constitution, and see what we can learn along the way.

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3: “[The Congress shall have Power] To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations…” What should U.S. foreign policy on trade be? Laissez-faire. Free trade with all, for all. No tariffs, period. Why? Because:

1.) it’s the right thing to do and

2.) it’s better for the economy and

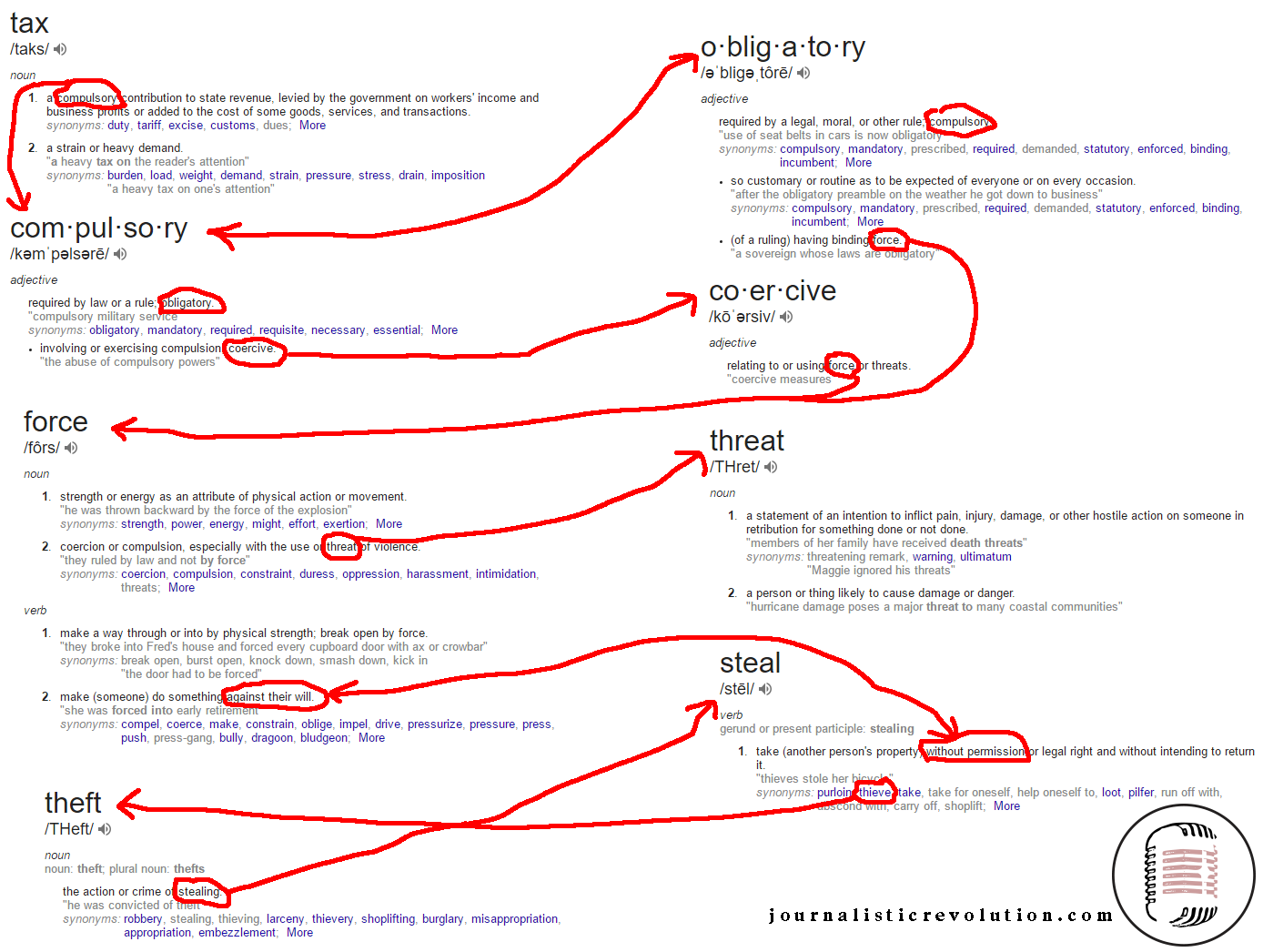

3.) as always, taxation is theft.

Perhaps you doubt me. Think about it this way: countries do not trade with each other, but individuals trade with other individuals in the same country and foreign countries. It is not within the purpose of government to give some individuals an economic advantage over others, even if those individuals reside in separate countries. This point segues into the second one with the observation that tariffs give one segment of the domestic population advantage over other parts. Let’s take the recent steel tariffs for example. While they may have helped some domestic steel manufacturers by raising their foreign competitors’ prices and thus encouraging American consumers to purchase more domestic steel and less foreign steel, the cost is passed on to the entire rest of the country who now has to pay more for steel than they otherwise would have. This artificial price manipulation is dangerous for the economy, in part because the increased cost of steel takes funds away from other endeavors, with limitless potential for helping the economy. Regarding the third point, (#TaxationIsTheft) I’ll just refer you to this meme I stole from someone on Facebook.

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 10: “[The Congress shall have Power] To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offenses against the Law of Nations…” The “Law of Nations” does not refer to International Law as some may suppose. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England — an authoritative tome on common law with which the Founders were intimately familiar and to which they referred frequently — explains it. “The law of nations is a system of rules, deducible by natural reason, and established by universal consent among the civilized inhabitants of the world…. offences against the law of nations can rarely be the object of the criminal law of any particular state. For offences against this law are principally incident to whole states or nations…. The principal offences against the law of nations … are of three kinds; 1. Violation of safe-conducts [as in war]; 2. Infringement of the rights of ambassadors; and, 3. Piracy.” There’s more involved in the “Law of Nations,” including the Law Merchant (a fascinating topic about which I’ll write one day) but this is the most relevant part for our purposes today. This clause touches slightly on foreign policy. Essentially, the U.S. should courteously refrain from violating the customs of international interactions as well as provide for discouraging the small possibility of their citizens doing the same. In the context of a Constitutional Republic, this is all good and proper.

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 11: “[The Congress shall have Power] To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water…” Here we have a power that is over-used and a power that is under-used. Congress has not declared war since World War II, but the U.S. has been at war somewhere all but five years since then. If the country is going to be at war, make it official. Or not, I guess. The Constitution provides for making it unofficially official. The Letters of Marque and Reprisal is probably the most underutilized of all the Congressional powers. This clause empowers Congress to commission privateers and mercenaries to go after enemies for profit. Congress should not be going to war willy-nilly all the time. After 9/11, Congress could have put a billion dollar bounty on Bin Laden and saved a few trillion dollars and untold human lives.

Article 2, Section 2, Clause 2: “[The President] shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties … and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls….” This section deals rather directly with foreign policy and diplomatic relations; it is the part that George Washington famously cautioned about in his farewell address. As we know, a system that depends on persistent suppression of human nature dooms itself from the start. We now have many “entangling alliances,” even though the first man in charge understood the danger and explicitly warned future leaders in a permanent record! The lesson about human nature here is more important than the lesson about treaties.

That’s pretty much all I could find in the Constitution about foreign policy. In the next part of this series, I plan to discuss why the U.S. should recognize Liberland diplomatically.