“Why can’t everything be free?” I’m always delighted whenever a child asks me, because I have an intellectually solid answer even a child can understand. Namely: If everyone had to produce for free, there would be virtually nothing to buy. If everything had a price of zero, consumers would strive to fill their shopping carts with anything they could get their hands on. Producers, however, would basically stop working.

(To be clear, this assumes that government strictly enforces this disastrous law. In the real world, even terrified North Koreans break the law when starvation is their only alternative).

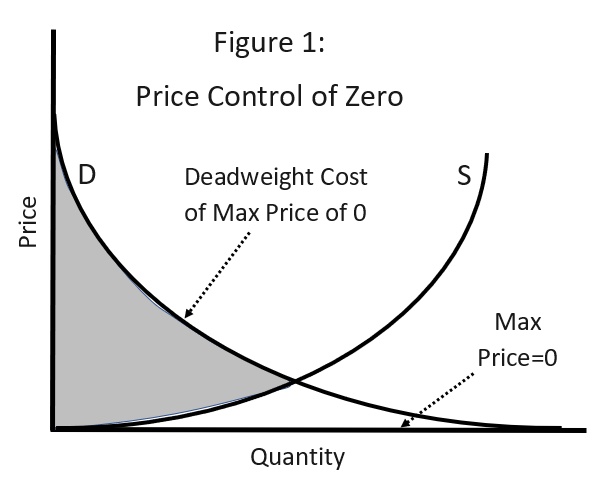

What few children would understand is the following diagram. In a perfect world, I would have just copied it out of the textbook. But as far as I know, no textbooks actually contain this diagram, so I made it myself.

In a normal supply-and-demand diagram, the shaded area shows total gains from trade. With a price control of zero, however, the shaded area becomes the deadweight cost. How can deadweight costs equal gains from trade? Because a price control of zero annihilates the entire market, driving production down to zero. The unintended consequence of a price control of zero is a market quantity of zero.

Is any government demented enough to impose such draconian price controls? Yes; virtually all governments do so. Most notably, while organ donation is normally legal, organ markets are almost always banned. In other words, organs are something you can give away for free but may not sell at any price. Which is equivalent to a price ceiling of zero.

Still, price controls this draconian are extremely rare. What is not rare, however, is a seemingly slight variation on zero-pricing. When children ask, “Why can’t everything be free?,” they might be visualizing a world where charging money for goods is illegal. Most of the time, however, they are probably visualizing something quite different: A world where government directly gives everyone what they want, free of charge. Gratis.

What’s wrong with that? The easy answer is to say, “Well, someone has to pay for stuff, so government freebies ultimately mean enormous taxes.” That’s true, but misses the deeper economic insight. Namely: Giving people whatever they want, free of charge, is extremely wasteful, because it leads people to consume products they barely appreciate. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Gratis is not great.

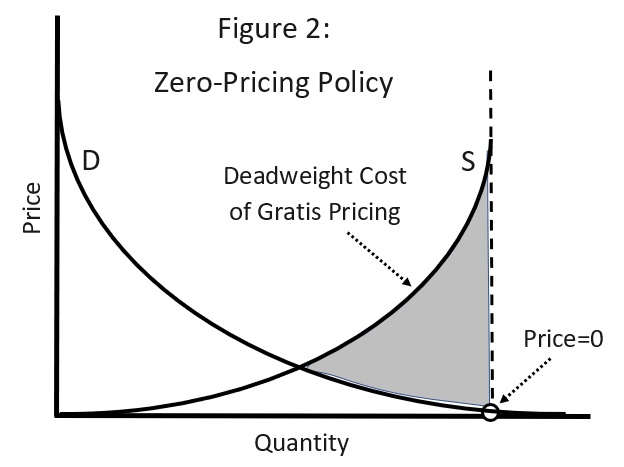

To see what I have in mind, ponder the following diagram:

What’s going on? On the generous assumption that government keeps per-unit costs at their original level, the efficient outcome is for consumers to go to the intersection of supply and demand. This maximizes the excess of benefits over costs. But if goods are free, consumers don’t stop there. Instead, they consume and consume and consume until they hit the dashed vertical line, which shows total quantity when demand intersects the x-axis. All units to the right of the intersection of supply-and-demand cost more to produce than the benefit they yield. Summing all these losses gives us the shaded area – which could in principle (though not as drawn) exceed the total surplus generated by the good’s existence.

Upshot: It is entirely possible that giving goods away for free without limitation is even less efficient than the good not existing at all!

Does this really happen in the real world? Verily. Any country that lets people have unlimited health care or education for free qualifies. To avoid this massive waste, you need death panels and such.

Is gratis pricing always bad? Not quite. For thoroughly non-rivalrous goods, gratis pricing is maximally efficient, at least in the short-run. (Though the long-run can be a totally different story). Similarly, gratis pricing is maximally efficient if other prices have already done their job. In a free market, landlords charge people for their location, so there is no need for an additional “immigration charge” on top. And of course, when transactions costs are high relative to the value of the goods, gratis pricing can be the least-inefficient option. Charging people for soap at a hotel makes little sense, because almost everyone wants a little soap, hardly anyone wants a lot of soap, soap is cheap, and collecting soap fees is expensive.

What about positive externalities? Gratis pricing can be efficient if positive externalities are massive. In all other cases, however, free is overkill. Usually severe overkill.

The pathologies of zero-pricing are one of the most important topics that every econ textbook I know of totally neglects. And I can’t help but think that the reason is Social Desirability Bias. Human beings love the image of giving everyone what they need, free of charge. Demagogues capitalize on this love. That’s probably why education and health spending are so bloated; giving everyone all they want is folly, but this folly sounds ever so sweet. To discover that “Gratis is not great!” is crucial for economic literacy. But so enlightening your students is as thankless as telling them that Santa Claus doesn’t exist.