There’s a path my life could have taken – could still take – toward the life of an intellectual.

I’ve just about always been interested in one or more of the favorite intellectual subjects of philosophy, history, politics, theology, economics, psychology, and sociology (whatever that is). I’ve always liked to have big opinions on things. And I’ve always preferred toying with ideas to toying with numbers or machines.

But I’m beginning to think this is an aptitude worth resisting. It’s not obvious to me that intellectuals as such bring a whole lot of benefit to the world.

Obviously this will be controversial to say.

For the sake of this post, I’ll be using a Wikipedia-derived definition:

“An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking and reading, research, and human self-reflection about society; they may propose solutions for its problems and gain authority as a public figure.”

Let me be clear that I think everyone ought to engage in critical thinking. It’s in the rest of the definition that the problems start to emerge.

Every intellectual is a person who not only has a pet theory about what’s wrong with the world – but who makes it their job to reflect/research on that problem and write about that problem.

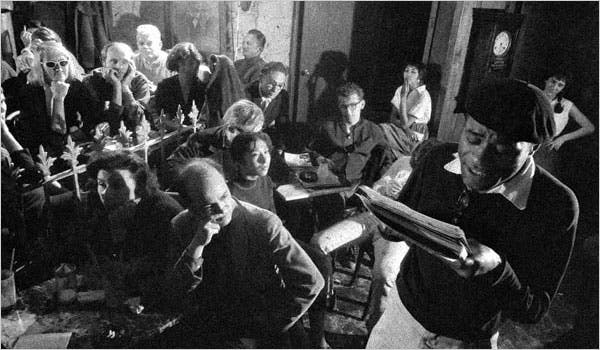

When you think about these intellectuals, what do you think of?

My mind wanders to the endless number of think-pieces, essays, and books with takes what’s wrong with humans, what’s wrong with society, or what’s wrong with intellectuals (that’s right – I’m currently writing a think-piece. Shit.) The history of this produce of intellectualism is an a stream of lazy, simplified pontifications from individuals about things vast and complex, like “society,” “America,” “the working classes,” “the female psyche,” etc. in relation to something even more vast and complex: “human life.”

It’s not that thinking about these things are wrong: it’s that most of the ink spilled about them is probably wasteful. Why?

Because core to the definition of intellectualism defined above is its divorce from action. Intellectuals engage in “reading, research, and human self-reflection,” “propose solutions,” and “gain authority as public figures,” but none of these acts require them to get their hands dirty to test their hypotheses or solve their proposed problems.

The whole “ivory tower” criticism isn’t new, so I won’t belabor the point. But I will point out two consequences of intellectualism’s separation from practical reality.

First, intellectuals don’t often tend to be great people. Morally, I mean. Tolstoy left his wife in a lurch when he gave up his wealth. Marx knocked up one of his servants and then kicked her out of his house. Rousseau abandoned his children. Even Ayn Rand (whom I love) could be accused of being cultlike in her control of her intellectual circle. Those are just the notable ones – it’s fair to say that most of the mediocre “public intellectuals” we have aren’t exactly action heroes. While they may not be especially bad, they aren’t especially good on the whole.

There seems to be some link between a career which rewards abstract thought (without regard for action) and the mediocre or downright bad lifestyle choices of our most famous intellectuals.

The second major problem with intellectuals springs from the fact that nearly everything the intellectual does is intensely self-conscious. Whether it’s a philosopher reflecting on his inability to find love and theorizing about the universe accordingly or an American sociologist writing about the decline of American civilization, the intellectual is reflecting back upon what’s wrong with himself or his culture or his situation constantly, usually in a way that creates a strong sense of mental unease or even anguish.

Have you ever seen an intellectual coming from an obvious place of joy? The social commentators are almost always operating from malaise and malcontent, which almost always arise from a deep self-consciousness.

Of course it’s anyone’s right to start overthinking what’s the matter with the world, and to feel bad as a result. The real problem is that the intellectual insists on making it his job to convince everyone else to share in his self-conscious state of misery, too.

How many Americans would know, believe, or care that “America” or “Western Civilization” was declining if some intellectual hadn’t said so? How many working class people, or women, or men would believe they are “oppressed”? How many humans would be staying up at night asking themselves whether reality is real? Both are utterly foreign to the daily experience of real, commonsense human life. And while the intellectual may draw on real examples in his theories, he’s usually not content to allow for the exceptions and exemptions which are inevitable in a complex world: his intellectual theory trumps experience. The people must *believe* they are oppressed, or unfulfilled, or unenlightened, or ignorant of the “true forms” of this, that, or the other.

I’m wary of big intellectual theories for this reason, and increasingly partial to the view that wisdom comes less from thinking in a dark corner and more from living in the sunshine and the dirt. The real measure of many of these theories is how quickly they are forgotten or dismantled when brought out into daily life.

People who use their intellects to act? The best in the world. But intellectuals who traffic solely in ideas-about-what’s-wrong for their careers? More often than not, they are more miserable and not-very-admirable entertainers than they are net benefactors to the world.

The ability to think philosophically is important. But that skill must be used in the arena. Produce art. Produce inventions. Be kind. Action is the redemption of intellectualism.

Disclaimers

*By “intellectuals,” I don’t mean scientists. On the humanities side, I don’t even mean artists. The problem isn’t artists: it’s art critics. It’s not scientists: it’s people who write about the “state of science.”

There are exceptions to the bad shows among intellectuals, but usually these are the intellectuals who are busy fighting the bad, ideas of other intellectuals: people like Ludwig von Mises fighting the ideas of classical socialism, or . The best ideas to come from people like this are ideas which don’t require people to believe in them.*

And don’t get me wrong: this is as much a mea culpa as a criticism of others. I’ve spent much of my life headed down the path of being an intellectual. I’m starting to realize that it’s a big mistake.