In the late 1940s, just after World War Two, a small knot of wanna-be writers attending Harvard University got together and formed the nucleus of what would be labelled the Beat Generation. After graduation, and once they got their typewriters clacking in earnest, these three icons of Beatnik fame – Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs – would pen, between 1957 and 1959, the three largest looming pillars of Beat literature: Kerouac’s novel On the Road, Ginsberg’s poem “Howl,” and Burroughs’s surrealistic novel The Naked Lunch. They would not be alone. A whole host of other poets and authors put pen to paper in their wake, and ended up defining the Beat experience and lifestyle: A kind of nomadic existence characterized by wanderlust, prodigious drug and alcohol use, spiritualism, free sex, rejection of traditional societal values, and a wholesale immersion into literature, jazz music, and artistic creation. This nascent Bohemian culture – though far smaller in scope and numbers than the press it received – unquestionably set the stage for what would follow in the 1960s, with its far bigger hippie youth culture, psychedelic drug and rock music atmosphere, and anti-Vietnam Conflict stance.

There were differences between these two ostensibly “antiestablishment” lifestyles, and not all of them merely temporal. The Beats projected a different vision than the hippies who followed after them, and it was one that, I contend, appealed much more to an individualistic sensibility.

While some beatniks gravitated towards or at least flirted with Marxism (most notably Ginsberg, who was later one of the few Beats to transition over to the hippie cause), many of the more prominent ones, like Kerouac and Burroughs, decried communism vociferously. Kerouac additionally defended his French-Canadian Roman Catholic roots, while Burroughs remained a staunch defender of firearms ownership his whole life. They unapologetically capitalized on their bestselling books, fought against censorship, and revelled in the material benefits of living in an American land of plenty – even during the time before their writings made them wealthy and famous, and they survived on shoestrings as they traversed the countryside, stopping in roadside diners and cheap motels along the way, scribbling down their experiences in notebooks for later typed manuscripts.

As the 50s gave way to the 60s, and the Beat Generation got a little older, the landscape began to change. JFK was killed. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones came to America. Troops started shipping off to Vietnam, and coming home in flag-draped caskets. The culture shifted. Young people began facing off against the system through draft resistance and protests in the streets. Rock concerts became huge, drug-soaked festivals. College campuses broke out in riots. Mansonites murdered.

The Beats who were left by then (save Ginsberg) mostly faded into the background. Some kept writing. Kerouac died a broken and devastated alcoholic in 1969. Lawrence Ferlinghetti kept running City Lights Books and Publishing in San Francisco (and lived to the ripe old age of 99). Few threw themselves into the wave of youth tumult that characterized the 60s.

I like that. The Beats weren’t out to change the world – they only wanted to change their relationship to it. They didn’t want to overthrow the system – just remove themselves from it in certain respects. They wanted to change themselves, not others. If they wrote a few things down and told us about their experiences, it was only to expiate themselves – and maybe make a few bucks in the process, when and where possible. It wasn’t a cry to revolution. It was just living life.

The hippies proved, in many ways, the antithesis to all of this. “Tune in, turn on, drop out,” somehow became “Get clean for Gene.” Instead of staying in communes, the Baby Boomer “counterculture” made about the biggest mistake possible: They tried “changing the system” from within.

Look at the result of their folly.

One might argue, “Well, that generation had a draft and a war on their hands. What else could they do?” I think if the Beats had faced a similar situation, they would’ve just simply disappeared. There would’ve been no marches, no riots, and no running for political office. They wouldn’t have had the hubris to see themselves as harbingers of deliverance from anything. They would’ve just split to Mexico (as many of them did anyway), to never be heard from again, except maybe in a few underground literary journals.

The hippies made the mistake of trying to live and manage everyone else’s life for them, instead of just building lives for themselves – and leaving the rest of us alone. And they’re still doing it. As are their descendants. And boy, have they ever fucked things up.

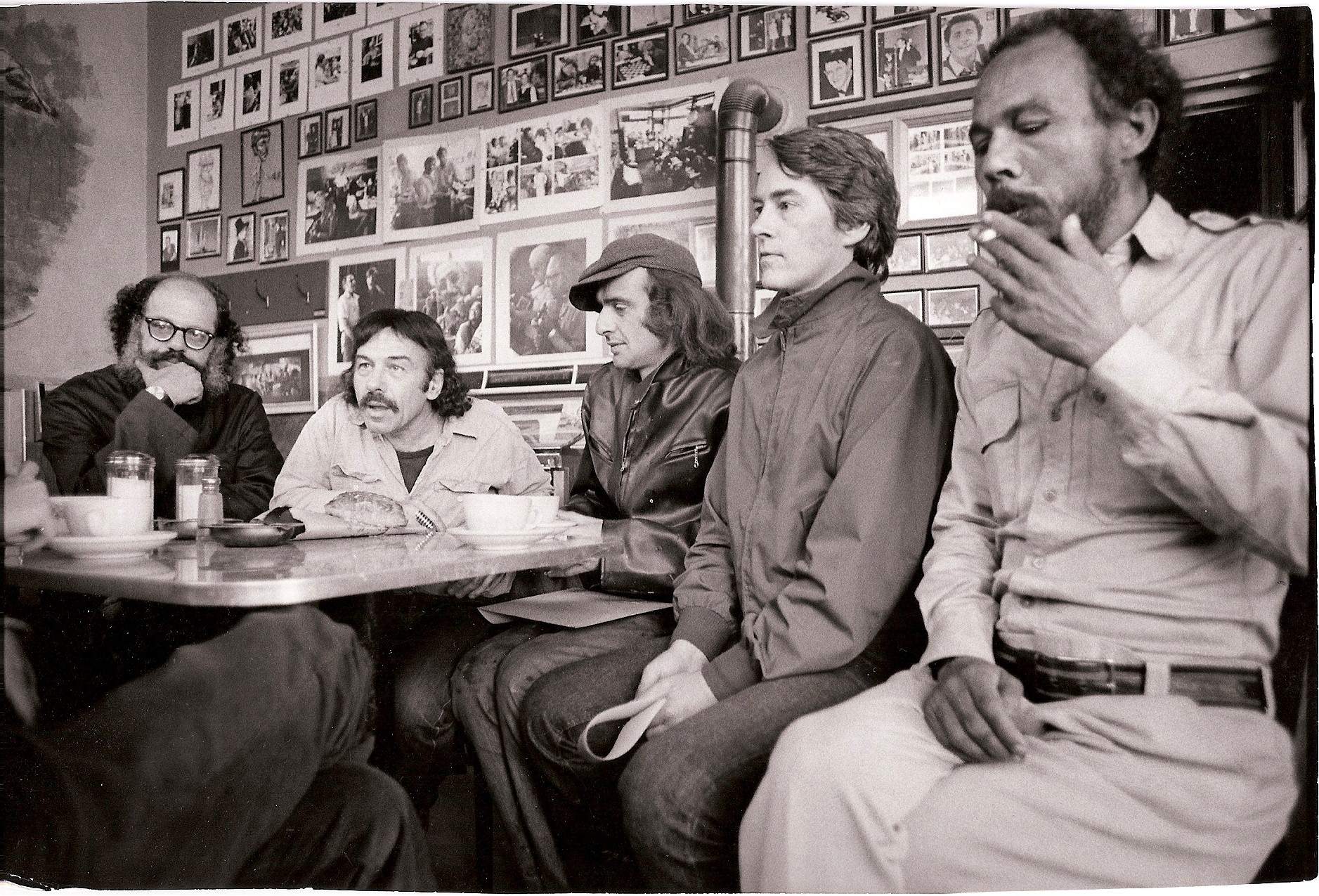

The Beats are long gone now, of course, as is the America and the world they knew. I often think what it must’ve been like in those boozy, smoke-filled jazz clubs full of poetry readings and loose women. There was a time in my life when I would’ve revelled in that. I probably still could, in truth. But I’m older now, I’ve kind of been-there, done-that, and my perspective is a little wider.

Ginsberg famously wrote in his 1958 poem, “Howl,” that he saw the best minds of his generation destroyed by madness. He couldn’t have known it at the time, but he was actually writing about the 60s yet to come. The end product of that has most certainly been madness. One look at modern 21st century “woke” cultural Marxism proves it to inarguable conclusion.

I don’t think the Beats – most of them, anyway – would like what today’s Left are. But they certainly wouldn’t try forcing them to change, either. Likely, the members of the Beat Generation would just tell the lot of such self-righteous prigs to go fuck themselves – and just go and do and say and write whatever they wanted to, regardless.