Written by Davi Barker.

Many voluntaryists have looked longingly toward Somalia for evidence of our ideas in practice. But it’s a little tough when that real-world example also happens to be the quintessential image of extreme poverty and feuding warlords for most people.

Nonetheless, sometimes an article appears that rightly points out that comparing Somalia to developed nations is a little intellectually dishonest. In fact, Somalia has improved by virtually every measure of standard of living without a state, or when compared to its neighbors that still have a state.

Even the BBC grudgingly admitted that 20 Years of Anarchy had spurred economic growth, especially in the telecommunications sector.

Michael van Notten’s book The Law of the Somalis describes Somalia’s stateless legal tradition, which he calls “kritarchy.”[1] As Africa explodes into populist movements demanding Western-style democracy, I’d like to argue, as van Notten did, that a superior indigenous alternative is nestled right in their backyard.

Somalia is not stateless by accident, as is the conventional view. The Somali people consciously rejected democracy and central government, and with good reason. Prior to the colonial period almost all African nations were polycentric tribal anarchies, which practiced a system of customary law.

The Somalis never accepted the legal systems of the colonial powers and largely ignored them or tried to nullify them by noncompliance, preferring always the social software of their own design. In 1991 the Republic of Somalia collapsed, but rather than electing a new leader, Somalis simply allowed their indigenous customary law to become the unopposed law of the land, which did not include any central government.

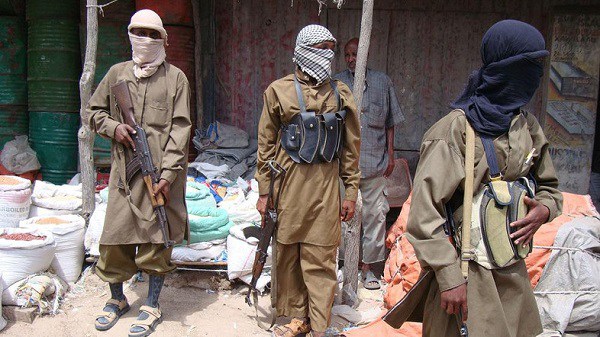

No discussion of Somalia can occur without addressing the political violence in and around the city of Mogadishu. So why Mogadishu? Well, that’s where the defunct politicians of the old republic, now known as “warlords,” are attempting to reestablish a central government in the old capital.

The United States and the United Nations believe that a central government is necessary to bring Somalia into, “the family of democratic nations,” and they have spent billions of dollars on state-building efforts, which only perpetuate the violence. Essentially, there is a huge pool of free money for whichever warlord can convincingly claim to be the central government of Somalia, but the people persistently resist all such claims. So warlords must use brute force, against both the people and each other, if they want the slush fund. Were it not for this there would be little incentive for civil war.

Van Notten speculates that the reason the US and UN do this is ideological, and fundamentally rooted in their fear that if Somalia were allowed to succeed, its system of stateless law could be viewed as a viable alternative to democracy and be spread elsewhere.

Why are the Somali people consistently unimpressed with Western political systems?

To answer that, we’ve got to define four sources of law that Van Notten identifies in the book: natural law, contract law, statutory law, and customary law. Natural law is the voluntary primordial order of all human societies, which coevolved with human nature. It is the invisible hand behind the entire human ecosystem. Natural law can be discovered and described, but it cannot be amended by human ambitions. A natural right is one that can be universalized to all human beings and exercised without permission and without infringing on the rights of others — namely, these are the rights to life, liberty, and property. Put simply, don’t hurt people and don’t take their stuff.

Contract law simply means to keep your agreements. A contract is valid when it is voluntarily entered and does not violate the rights of any third party.

Statutory laws are rules written by rulers and enforced through threats of violence, usually by a standing police force.

Customary law may be an unfamiliar concept, but once you learn to see it, you’ll see it everywhere. Like natural law, it emerges spontaneously from people’s voluntary interactions. Think of it like this: the laws of chemistry or physics are eternal, but the sciences of those disciplines are constantly evolving. Such is the relationship of natural law to customary law. Natural law is eternal, while customary law is the discipline of refining our understanding of it.

Natural law can only be pursued in ways consistent with itself, just as inconsistency disproves a law in science. In that sense, fraudulent contracts, barbaric customs, and oppressive statutes cannot be rightfully regarded as laws at all, just rules.

The Somalis are not ignorant of these concepts. In fact, life, liberty, property, and the four divisions of law all have words in their language that were not borrowed from other languages, indicating that these concepts are as indigenous to them as they are to English speakers. It was no historical accident that they developed a voluntary legal structure. Almost every Somali child is thoroughly educated in the customary law by the age of seven. Even an illiterate nomad understands life, liberty, and property, and regards himself as subject to no authority except God.

The Somali people strongly reject statutory systems like democracy because they render everyone subservient to political officials. They oppose dividing society into the rulers and the ruled. Democracy is often presented as “government by consent,” but in any statutory regime, someone claims the authority to rule over those who don’t consent. The inability to opt out by nonparticipation or secession renders the whole concept of consent meaningless. There can be no natural right to elect a “representative” to do what you have no natural right to do yourself.

Further, the idea that rulers could write new laws would strike the Somali people as obscene, because in their view the law is preexistent.

They cherish natural rights like the right to self defense by private arms, to practice law, to travel, to freely contract, to educate children, and to trade in open markets; in statutory systems all of these are reduced to privileges requiring licenses. In natural law, one is free to engage in all of these activities without asking permission, and every license is an infringement on that right. In order to protect natural rights, statutory law must first violate natural rights; whereas customary law is designed to protect natural rights in ways that approximate natural law. In this sense, statutory democracy itself is incompatible with natural law.

So what is kritarchy? How does Somali customary law work?

The term “kritarchy” comes from the Greek terms kritès (judge) and archè (principle) and describes a social order where justice is the ruling principle. It’s tempting to think of it as “rule by judges,” but that’s not really accurate. In a kritarchy, judges have no special powers and only hold their position by the consent of others. And there are no rules prohibiting anyone from serving as a judge. Disputing parties may choose anyone who has a good reputation, and it often happens that a clan has many judges. But a Somali judge only enforces the customary law, which is natural law as he understands it.

Traditional Somali society is decentralized, similar to the Internet. There is no executive or legislature. There is only a set of familiar protocols shared by a network of independent individuals organized into clans.

Now, you might think that a clan must have a chief who is the final arbiter in all matters. This is simply not the case. In fact most Somali clans have origin stories about a distant past when their elders appointed a clan chief, but he was so oppressive or incompetent that they abolished the position and agreed never to appoint another.

Individuals are in no way obligated to their clan. Dissenters are never forced to participate in any clan activity, and individuals are free to leave their clan and either join another or form their own. There is no coercive hierarchy within the clan. Antisocial behavior only leads to social ostracism. If force must be used, it is never to destroy persons or property but only to halt aggression.

The legal apparatus only comes into effect when there has been a violation of rights, as in personal injury or damage to property. All justice is restorative, not punitive. So if there is no victim there is no crime. Somali law requires only that victims be compensated for violations of their life, liberty, and property.

A law court is formed when a conflict requires a third party to resolve it. If the disputants are from the same clan they may go to the same judge, but if they are from different clans judges from each family form a law court together. Judges are tasked with investigating the conflict and discovering a resolution that most satisfies the reason and conscience of both parties, not with rendering a verdict consistent with the precedents of other courts.

If the defendant is found to be at fault, compensation is owed to the victim for the damage caused. Somalis view humiliating or punishing a wrongdoer as a waste of time and resources, except that an additional fine may be awarded to the victim if the violation was intentional. The task of deterrence or rehabilitation is left to the clan of the wrongdoer, because they are ultimately liable for him.

So in the case of injury, the wrongdoer may be obliged to provide medical care as the victim recovers. In the case of theft, the stolen property must be returned and the victim compensated for their trouble. In the case of property damage, the property must be repaired or replaced. Although it is rare, in the case of homicide a murderer may be executed, but more often the bereaved family will agree to compensation, which is called the “blood price.” It is always up to the victim, not the judge, to decide to what extent to enforce the verdict.

All cases are widely discussed in the community, and if there is a consensus that the judge is not performing to the people’s satisfaction he may lose the confidence of his clan, and he will likely not be asked to settle future conflicts. In this way, judges are always subject to open competition.

Should enforcement be necessary within one clan, the court may request that able-bodied men in the community volunteer as a temporary police force, but there are no standing police. They may only use the minimum force necessary to right what was wronged. However, if the conflict was between multiple clans, one clan has no power to enforce its verdict on another. Penalties can be imposed for refusing to comply with a verdict, but clans are expected to police their own, and there are mechanisms in place to incentivize this.

Every clan maintains a communal fund that members voluntarily contribute to. This fund operates as a kind of social insurance for every Somali against liability. It can be used both to provide welfare for clan members who fall on hard times and as venture capital for businessmen to borrow and invest. If a person owes restitution that they cannot afford to pay, they must approach their clan to have their liability covered by this insurance fund.

This can be painfully embarrassing, and it gives the clan an opportunity to chastise the person, but it also insures that victims can always be made whole. In the case of conflict between multiple clans, this allows the clan of the victim to seek restitution from the insurance fund of the clan of the wrongdoer, which incentivizes clans to police their own. If habitual violators of the law become a drain on the clan’s insurance fund they may have their membership terminated, making them an outlaw with no protection from any court.

In principle, this description of the kritarchy in Somalia will seem very familiar to any student of natural law. However, in practice some of the customs which have evolved are so unique to their cultural and historical context that they seem utterly foreign.

Some customs are also stifling to economic development, which may explain why growth has been slower than we might predict in a stateless society. For example, customary law has been very reluctant to extend property rights to land. Instead land is owned by the clan, and an elaborate system of land-use customs have developed. This makes a kind of sense for a nomadic pastoral society, but for the development of modern infrastructure, land ownership is key.

In addition, foreigners have no protection in the Somali legal system (unless they are accepted by a host clan), and they are completely prohibited from owning land. The logic behind this is that they are not insured against liability the way clan members are; but discouraging foreign trade has stifled both economic growth and cultural cross-pollination.

Other customs are utterly barbaric by modern standards. Some clans use very primitive physical punishment for delinquent youth, as in tying them to a tree covered with honey and allowing them to be bitten by ants. The worst practices described in the book are those impacting women. In one case a verdict against a rapist obliged him to marry the woman he raped, the logic being that the damage he’d caused her was to spoil her marriageability. Some of these customs are so incredibly backward that they can only be understood with the detachment of an anthropologist, which van Notten provides.

Obviously, these customs have no place in natural law. It is incredibly important to understand that Somalia’s customary law is not being presented as a panacea, but that the elegant legal structure of kritarchy and its potential compatibility with natural law is a superior foundation for future development than is democracy.

To understand this point, imagine for a moment that customs like these were enshrined in the statutes of a democratic system. History shows us that social change precedes political change, and forcing the political apparatus to reflect social change is a slow process requiring mass movements, civil disobedience, and even civil war.

Customary law, on the other hand, evolves literally simultaneously with social change. It consists of the rules that judges discern from the normative behavior of living people. If social change occurs gradually, custom will change gradually; and if social change occurs suddenly, custom will change suddenly — because custom is changed by voluntary acceptance, not by democratic process.

Kritarchy can only exist in societies where the custom of seeking justice is stronger than the custom of achieving political goals through coercion. For democracy the opposite is true. For that reason, kritarchy is eminently suited to protect natural rights.

Kritarchy in Somalia challenges the conventional view that tribal societies had no concept of property and contract, because even without a central government Somalia has since time immemorial engaged in free trade, where prices are determined by market forces, and competition prevented the emergence of monopolies.

The Somalis have demonstrated that providing justice in the free market is at least possible, and that you don’t need to pass statutes prohibiting murder and theft, because those laws already exist, whether you write them down or not. In short, they have demonstrated that life, liberty, and property are inscribed upon the hearts of mankind, like fingerprints in the clay of Adam.

[1] Editor’s Note: Michael van Notten. The Law of the Somalis: A Stable Foundation for Economic Development in the Horn of Africa. Edited by Spencer Heath McCallum (Red Sea Press, 2005). The book was published before the international intervention of 2006, which propped up the Somali central government for a few years.