Read for Reconfiguration

I once had coffee with a guy who told me that he read Rich Dad, Poor Dad six times. He said it with such pride too. I was really excited since this was one of the first resources to influence me to think about financial literacy.

It’s been over ten years since I’ve read the book, but I still remember a few of the core concepts. So I started to discuss Robert Kiyosaki’s concept of assets as income-generating resources versus the traditional notion of “things you own,” and his mind was blown. He never heard the idea before. This surprised me because it was one of the main points of the book and it was repeated over and over. No big deal. Maybe that concept wasn’t important to him. After a few minutes of discussion, however, it was clear that he couldn’t recognize anything from the book. Again, no problem. Maybe he doesn’t remember the details, but he has an emotional memory of being impacted by it.

I have no opinions about that one guy’s relationship to that one particular book, but our conversation made me think about the purpose of reading books and how that might differ from the social rewards we sometimes get from claiming to have read certain books.

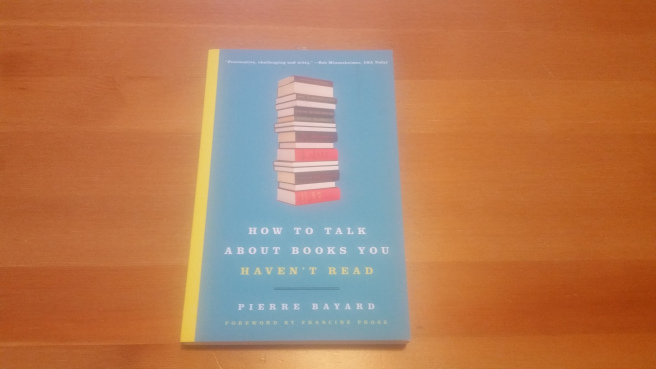

In How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, Pierre Bayard makes a fascinating distinction between internal (psychological) and external (physical) libraries:

“In truth we never talk about a book unto itself; a whole set of books always enters the discussion through the portal of a single title, which serves as a temporary symbol for a complete conception of culture. In every such discussion, our inner libraries — built within us over the years and housing all our secret books — come into contact with the inner libraries of others, potentially provoking all manner of friction and conflict…For we are more than simple shelters for our inner libraries; we are the sum of these accumulated books. Little by little, these books have made us who we are, and they cannot be separated from us without causing us suffering.”

I see the aim of reading as the construction of an inner library. The books in our outer library provide the tools for construction. When we face a problem, set a goal, or have a need, what matters most is our ability to retrieve something useful, relevant, or pleasant from the inner library we’ve gradually built through our studies. In this sense, books are not status symbols, they’re soul stirrers. We don’t read them because we wish to brag about ourselves. We read them because we wish to build ourselves.

Wherever learning resources are shared, there’s usually at least one person who’s quick to say something like “oh, I’ve already read that book” or as in the case I mentioned earlier “I’ve read that book multiples times.” My question is, can you say something intelligent about it? Can you use the ideas to create a result that matters to you? Can you advance the discussion started by that book with your own ideas? The purpose of reading a book isn’t to say you’ve read it.

A book is not a trophy. It’s a tool for personal transformation. For Kafka, “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.” Education isn’t a name dropping contest. It’s a paradigm-shifting process. It’s an opportunity to have our perspectives and presuppositions challenged from every angle.

If the process of scanning your eyes across the words on a page isn’t contributing to personal transformation, start over. If the process of letting sound waves pass through your ears isn’t leading to critical reflection, start over.

It’s not about how much technical detail you remember nor is it about how much time you read. It’s about what you’re able to retrieve from your inner library during those moments of need when no book, author, thought-leader, or friend, is within grasp.

Keep reading great books. Keep sharing great books. Keep taking beautiful photos of great books. Keep tweeting and talking about great books. But don’t forget to let those books disturb you, provoke you, and transform you.

As Mortimer J. Adler wrote, “In the case of good books, the point is not to see how many of them you can get through, but rather how many can get through to you.”